"Reconcile" by Sevgi Safer. Used with permission.

New:

The Everyday Lives of Sovereignty:

Political Imagination Beyond the State

Edited by Rebecca Bryant and Madeleine Reeves

Political Imagination Beyond the State

Edited by Rebecca Bryant and Madeleine Reeves

|

Around the world, border walls and nationalisms are on the rise as people express the desire to "take back" sovereignty. The contributors to this collection use ethnographic research in disputed and exceptional places to study sovereignty claims from the ground up. While it might immediately seem that citizens desire a stronger state, the cases of compromised, contested, or failed sovereignty in this volume point instead to political imaginations beyond the state form. Examples from Spain to Afghanistan and from Western Sahara to Taiwan show how calls to take back control or to bring back order are best understood as longings for sovereign agency. By paying close ethnographic attention to these desires and their consequences, The Everyday Lives of Sovereigntyoffers a new way to understand why these yearnings have such profound political resonance in a globally interconnected world.

Contributors: Panos Achniotis, Jens Bartelson, Joyce Dalsheim, Dace Dzenovska, Sara L. Friedman, Azra Hromadžić, Louisa Lombard, Alice Wilson, and Torunn Wimpelmann. |

"The Everyday Lives of Sovereignty is a significant theoretical and empirical contribution to anthropology, sociology, and political studies concerning 'sovereignty.' In the era of globalization, that concept is increasingly challenged as the shortcomings of what the contributors refer to as the Westphalian view of sovereignty become ever more glaringly apparent."

Katherine Verdery, City University of New York, author of My Life as a Spy

"This is a useful and important book that uses fragile states as a lens to examine the notion of sovereignty. The contributors to the volume show the many ways in which sovereignty is produced not only at the national scale but at the transnational and local scales."

Elizabeth Cullen Dunn, Indiana University, author of No Path Home

Katherine Verdery, City University of New York, author of My Life as a Spy

"This is a useful and important book that uses fragile states as a lens to examine the notion of sovereignty. The contributors to the volume show the many ways in which sovereignty is produced not only at the national scale but at the transnational and local scales."

Elizabeth Cullen Dunn, Indiana University, author of No Path Home

In progress:

Faking the State:

On Pirates, Puppets, and Other Unbecoming Subjects

On Pirates, Puppets, and Other Unbecoming Subjects

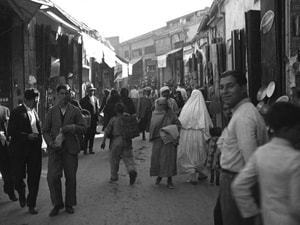

A checkpoint to enter the so-called Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. Photo by R. Bryant

This book asks what people understand and believe they are doing when they enact a state that they know everyone else considers to be “pseudo,” in other words what they’re doing when they’re “faking it.” The so-called Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus is one of the two states—the other being Taiwan—that have shown the greatest longevity as de facto entities. But despite its longevity and the seeming permanence of its institutions, today there is a common perception amongst its citizens that, as one of many recent newspaper articles phrased it, “a state called the TRNC never existed and never will.”

Since the easing of movements restrictions within the island in 2003, Turkish Cypriots have become more tied to the world, with increasingly direct relationships with international bodies and institutions, such as the EU and its representatives. Ercan Airport—the unrecognized airport outside north Nicosia—has become almost as busy a hub as the recognized Larnaca Airport in the south. Global capital has arrived in the form of Nike and Adidas stores, Popeyes chicken, Johnny Rockets, Mercure hotels, and Re/Max estate agents. With their EU passports, Turkish Cypriots are now free to take package tours to Thailand and Zanzibar, while youth can win scholarships to study anywhere in Europe. Moreover, Turkish Cypriots have experienced their own pseudo-ness for several decades, so why would a discourse of fabrication, or the “made-up state,” come to the fore and become an accepted part of public life only in recent years?

The book explores this paradox in order to think with literature on the construction and performance of the state. While I take the literature on the performance of the state as a starting point, my own concern is the point at which such performances succeed, or indeed, where they might fail, even for those enacting them. The argument uses examples of engagement with an unrecognized state to show how, in the context of globalization and transnational institutions, citizens of that de facto entity learn, in their daily lives, to perform not stateness and sovereignty, but rather “stateness” and “sovereignty.”

Ledra Palace Blues: Making Divided Nicosia

When it was built in the 1940’s, the Ledra Palace was Nicosia’s most luxurious hotel. Diplomats, movie stars, and war-weary journalists drank gin by its pool, and the local elite danced away evenings in its ballroom. Because of its location immediately outside the city’s old Venetian walls, however, Nicosia’s most glamorous venue was also one of the first historic casualties of Cyprus’s conflict. While barricades first arose to separate Nicosia neighborhoods in 1956, war and partition in 1974 engulfed the hotel and left it stranded in a narrow strip of buffer zone. The United Nations appropriated the hotel as housing for its troops, who today patrol the ceasefire line and hang their laundry from the hotel’s windows. The marble floors that once reflected dancers now echo with military boots, and the grand chandeliers that shimmered on silk dresses illuminate the mundane khaki of peacekeeping. Today the building is a bullet-pocked memorial to the days of Nicosia’s unity.

This book uses the Ledra Palace Hotel and the buffer zone that surrounds it as an entry point to this divided city. Through descriptions of particular neighborhoods and the characters that populated them, the narrative shows the processes of gradual separation and ultimate violent partition that resulted in two different worlds on either side of Nicosia’s ceasefire line. The city, in turn, serves as a microcosm for the processes that partitioned the island, including large-scale displacement and resettlement in the island’s cities. The result of more than two decades of research on Cyprus, the book is the first comprehensive work of urban history that explains for a general audience how the divided city and island that we experience today emerged in their current form.

This book uses the Ledra Palace Hotel and the buffer zone that surrounds it as an entry point to this divided city. Through descriptions of particular neighborhoods and the characters that populated them, the narrative shows the processes of gradual separation and ultimate violent partition that resulted in two different worlds on either side of Nicosia’s ceasefire line. The city, in turn, serves as a microcosm for the processes that partitioned the island, including large-scale displacement and resettlement in the island’s cities. The result of more than two decades of research on Cyprus, the book is the first comprehensive work of urban history that explains for a general audience how the divided city and island that we experience today emerged in their current form.

Proudly powered by Weebly